A piece of artwork has two identities; a signature binds the one to the other.

The first identity is the object, there in front of you, awaiting your gaze. The reckless or the deliberate brushstrokes, the smooth sheen on a carefully sculpted piece of marble, the lovely hatch-marks on an etching, all the little details that pull you in and make each piece of artwork unique. The second identity is the story of the artwork and its journey through the world. Who made it? Why? Where was it exhibited? Was it part of a bigger series? Who is the person in the portrait? and who has owned it? This story is called the provenance.

Like it or not, a work of art does not stand completely on its own: both its story and its physical character are important. Some degree of provenance helps work keep its value over time, and more valued work is more likely to be well-treated. But until artwork is identified, it effectively has little provenance. When someone is faced with a decision about what to do with a piece of art, the identity of its creator is important. So to make it more likely your work will be treated well, found and remembered, it is important to sign it clearly. Alan Bamberger is, among other things, an art consultant and independent appraiser specializing in original works of art. His article about artist’s signing artwork goes as far as saying, “No matter what your signature looks like, what form it takes or where you put it, no work of your art is complete without one.”

Where to Sign? and Other Guidelines

Where to sign artwork is the most debated part of the process. Painter Alice Neel did a huge signature and the date on the front of her paintings, but you’d never see a Georgia O’Keeffe signed on the front. Hers were restricted to the back, either on the canvas or stretcher frame. I was taught in art school to sign paintings on the back so it doesn’t take attention away from the artwork. That’s only one school of thought, but it’s how I’ve done it since then.

I do have one patron that likes me to sign paintings on the front, and at her request, I’ve been signing paintings she’s purchased that way. I try to hide the signature a bit and it’s starting me questioning whether or not I should hide a little signature on the front on all of them. It always seems so glaringly obvious to me, but when I just showed a friend one piece, he had to get out a magnifying glass to find it, so maybe it isn’t so distracting after all. I’m going to do a little experimenting, so keep your magnifying glasses at the ready.

Other things to consider:

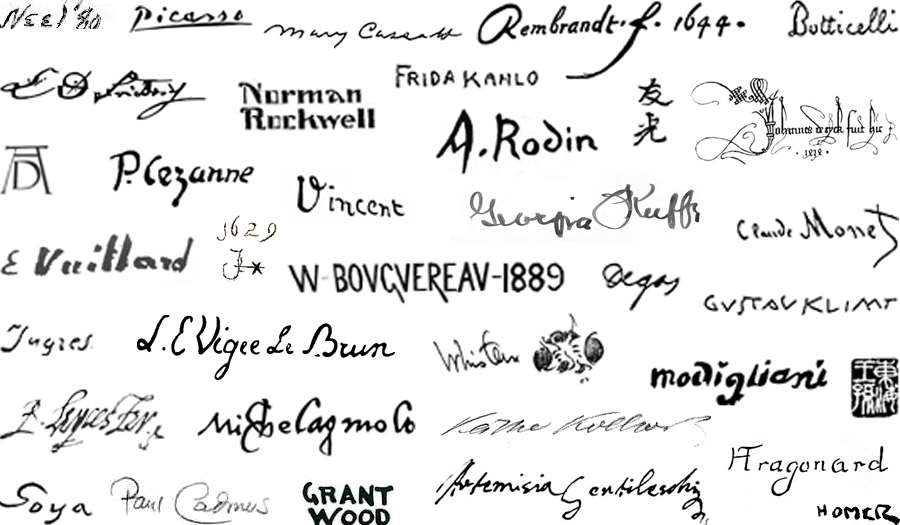

- If your signature isn’t legible, why bother? Note that even the well known artists in the image above have pretty clear signatures. There are websites dedicated to identifying paintings with illegible signatures (and they are not always successful).

- Keeping the look and placement of your signature consistent makes it easier to locate.

- Paintings and drawings are easier to authenticate if the signature is done in the same medium as the artwork.

- Your name may change. Consistency is important, but you just do the best you can do. It seemed like a good idea to go by Rebecca Raven after I got married, but going back to my maiden name after getting divorced means there are 9 years worth of little painting out in the world without my name on them! If you see a Rebecca Raven out in the world, you’re welcome to contact me and I’ll be happy to verify if for you. I keep excellent records.

Interesting Signatures

Signatures take many forms, from a simple hand-written or painted signature to pictographs or monograms; a traditional method of signature in China and Japan is to stamp artwork with a personal seal (a chop). Signatures themselves can have their own stories, and can be a reminder of the artist’s life and times. Here are two signatures that I found particularly interesting.

Whistler’s signature made an interesting transformation into the image of a butterfly, inspired by his studies of the artists “chops” found in Asian artwork, which was flooding Europe after Japan became open to trade in 1854. He sometimes hides the butterfly in unexpected places, such as the frame on the painting. Both the early and late versions of his signature are shown next to each other in the image above.

Joseph Cornell (not pictured above) presented me with a mystery. I’ve had the privilege to handle dozens of his pieces in my mount-making capacity at the Seattle Art Museum, and noticed many pieces attributed to him are signed, Robert Cornell. With the help of Wikipedia, I discovered that this Robert was Joseph’s younger brother who was disabled and had cerebral palsy. Though I never learned the exact significance of the signature, I was touched to learn that the artist devoted his life to caring for his little brother.

A Good Read About Provenance

I’m just finished reading a beautiful family memoir that I highly recommend called, The Hare with Amber Eyes: a Hidden Inheritance by Edmund de Waal. The author “traces the collection (of small Japanese sculpture called netsuke) from Japan to Europe…and back to Japan and Europe again”. It’s a profound take on provenance, and how much the things around us, that we invite into our homes, can become intertwined with our own histories.